The Museu do Aljube

Situated adjacent to the city cathedral, the Aljube was a notorious political prison during the dictatorship of Juan Antonio Salazar. Today, it’s been converted into an excellent museum about the struggle against fascism and colonialism.

It’s hard to believe, but until relatively recently, Portugal was under the thumb of the world’s longest-lasting dictatorship. António de Oliveira Salazar ruled the country with an iron fist between 1932 and 1968. A former economist, Salazar didn’t seem to fit the mold of a despotic ruler, and in many ways, he wasn’t. A lot of important reforms were instituted during his tenure, and he was even described as a “benevolent dictator” by certain American publications (who likely appreciated his strident anti-communism).

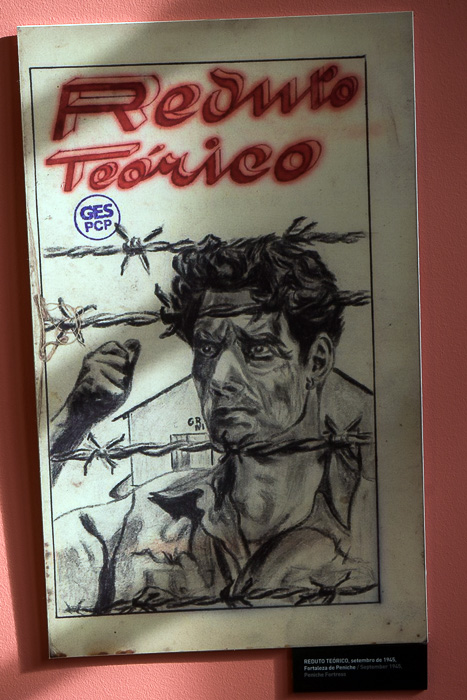

But I doubt that the prisoners of the Aljube prison would use the word “benevolent”. Under Salazar and the Estado Novo, dissent was discouraged, to put it mildly. Opposing political parties were outlawed, while intellectuals and agitators were exiled or jailed on the flimsiest of charges. Torture was routine, and prisoners were kept in shocking conditions.

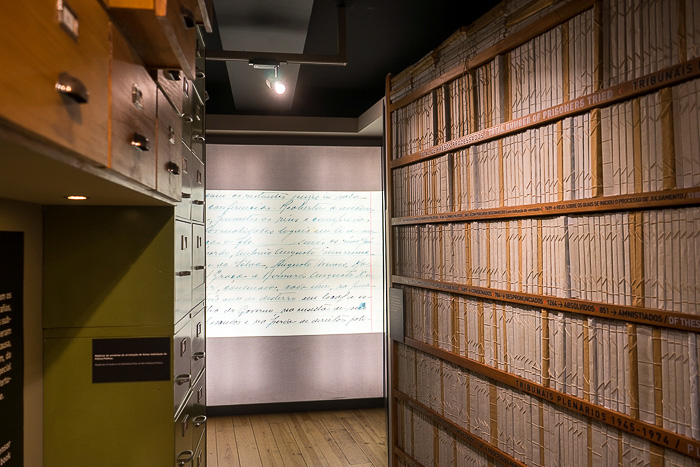

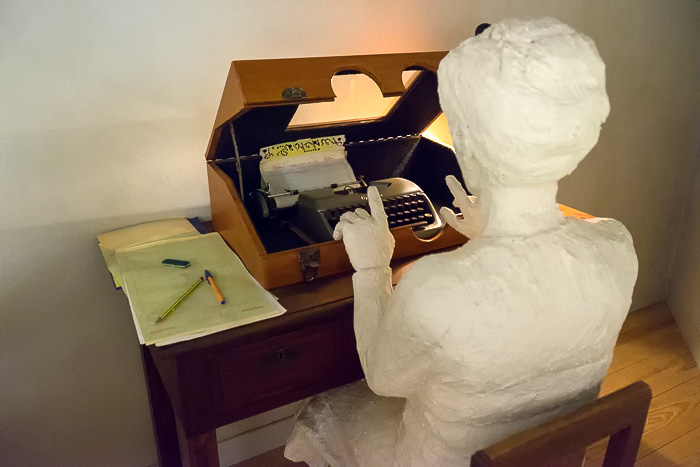

Portugal under the Estado Novo was a fascist police state, and the government sowed a wide network of informants and spies, seeding suspicion and fear among the population. Lisbon must have felt very similar to Stasi-era Berlin, although it was at the other end of the ideological spectrum. Private mail was combed through, phone conversations were tapped, and you never knew if your co-worker, friend, or daughter was a government informer, about to alert the authorities to your illegal socialist tendencies.

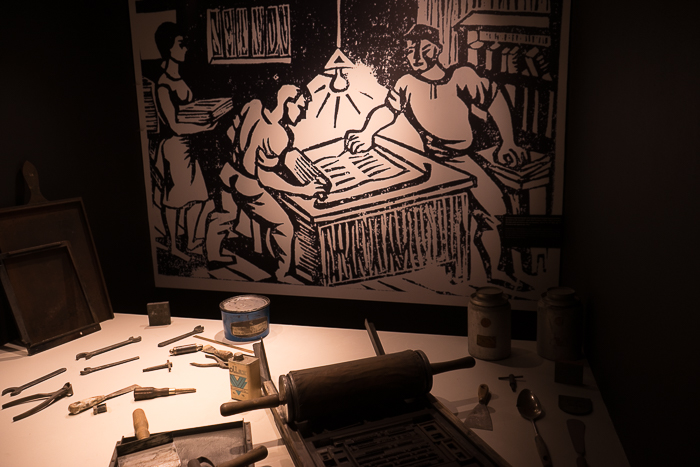

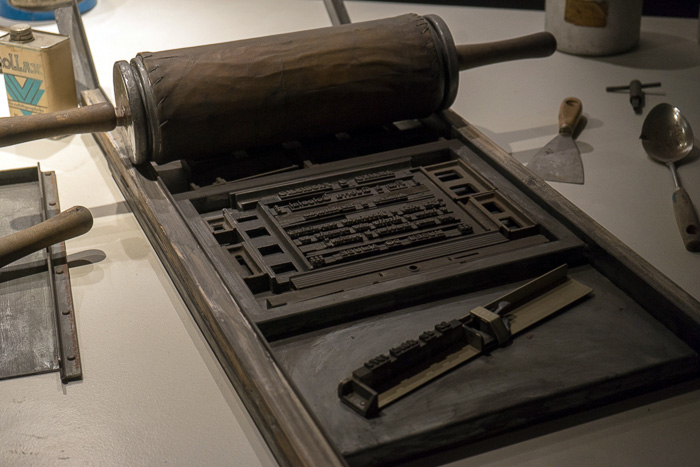

The Aljube Museum does a chilling job of bringing the atmosphere of Salazar’s Lisbon back to life, by telling the stories of the prisoners, unions, students, exiles and regular folk who fought back against the regime. You see the conditions in which the Aljube’s inmates suffered, read harrowing descriptions of the torture they endured, and learn about the difficulties they had in getting their message heard.

Eventually, the Estado Novo of Salazar would collapse. A military coup on April 25th, 1974 quickly blossomed into the Carnation Revolution, named after the flowers which were placed into the muzzles of soldiers’ rifles. Hardly a shot was fired during this transition of power; the long-awaited end to authoritarianism is remembered in an excellent multi-media exhibit on the third floor of the museum.

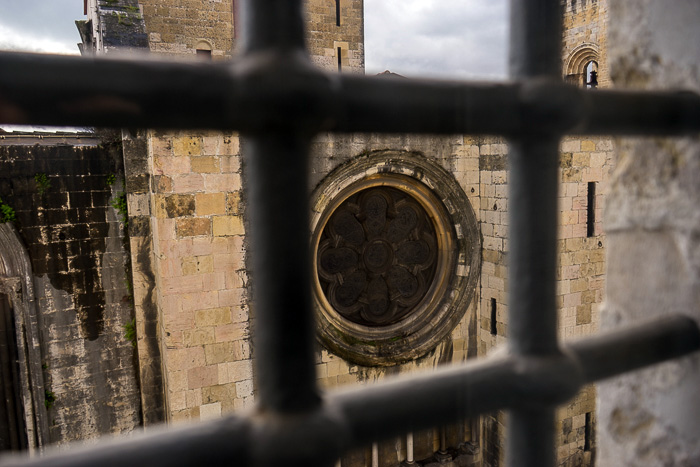

While at the Aljube, don’t forget to check out both the very top floor and the basement. On the fourth floor, there’s a narrow balcony which boasts a unique view over the roof of the cathedral. And downstairs is a small archaeology exhibit which displays some of the Aljube’s original foundations. It wasn’t just Salazar who employed the building as a prison; evidence shows that it’s been used for this purpose since at least the time of the Moors.

-Further Reading: Portugal History